Decades ago, Harvard University purchased a stained and faded copy of the Magna Carta for less than $30.

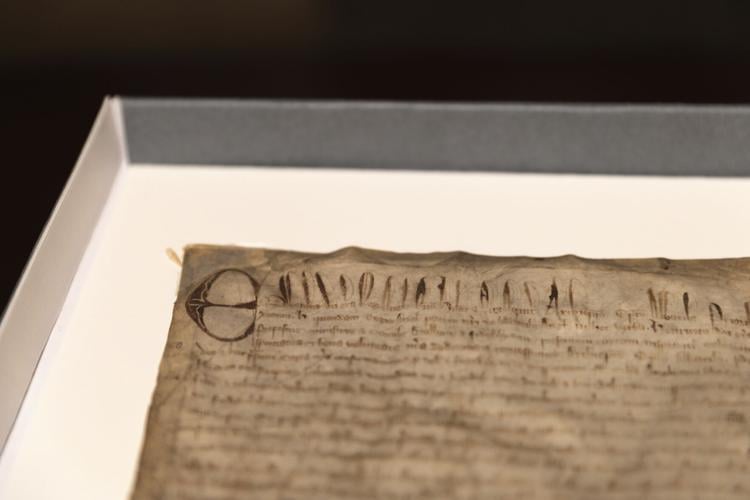

A rare copy of the Magna Carta sits in a display case April 15, 2025, at Harvard Law School in Cambridge, Mass.

Two researchers now concluded it's much more valuable: a rare version issued in 1300 by Britain's King Edward I.

The original Magna Carta established in 1215 the principle that the king is subject to law, and it formed the basis of constitutions globally. There are four copies of the original and, until now, there were believed to be only six copies of the 1300 version.

"My reaction was one of amazement and, in a way, awe that I should have managed to find a previously unknown Magna Carta," said David Carpenter, a professor of medieval history at King's College London. He found the digitized document while searching the Harvard Law School Library website in December 2023.

"First, I'd found one of the most rare documents and most significant documents in world constitutional history," he said. "But secondly, of course, it was astonishment that Harvard had been sitting on it for all these years without realizing what it was."

People are also reading…

Researchers use imaging technology March 19, 2024, on a copy of the Magna Carta from 1300 to reveal details that are invisible to the human eye at the Weissman Preservation Center at Harvard University in Cambridge, Mass.

Confirming the document's authenticity

Carpenter teamed up with Nicholas Vincent, a professor of medieval history at Britain's University of East Anglia, to confirm the authenticity of Harvard's document.

Imaging technology is used March 19, 2024, on a copy of the Magna Carta from 1300 to reveal details that are invisible to the human eye at the Weissman Preservation Center at Harvard University in Cambridge, Mass.

Comparing it to the other six copies from 1300, Carpenter found the dimensions matched up. He and Vincent then turned to images Harvard librarians created using ultraviolet light and spectral imaging. The technology helps scholars see details on faded documents that are not visible to the human eye.

That allowed them to compare the texts word-for-word, as well as the handwriting, which include a large capital 'E' at the start in 'Edwardus' and elongated letters in the first line.

After the 1215 original printed by King John, five other editions were written in the following decades — until 1300, the last time the full document was set out and authorized by the king's seal.

The 1300 version of Magna Carta is "different from the previous versions in a whole series of small ways and the changes are found in every single one," Carpenter said.

Harvard had to meet a high bar to prove authenticity, he said, and it did so "with flying colors."

Its copy of the Magna Carta is worth millions of dollars, Carpenter estimated — though Harvard has no plans to sell it. A 1297 version of the Magna Carta sold at auction in 2007 for $21.3 million.

Librarians use imaging technology March 19, 2024, to see details on a rare, faded copy of the Magna Carta from 1300 in Cambridge, Mass.

A document with a colorful history

The other mystery behind the document was the journey it took to Harvard.

That task was left to Vincent, who was able to trace it all the way back to the former parliamentary borough of Appleby in Westmorland, England.

The Harvard Law School library purchased its copy in 1946 from a London book dealer for $27.50. At the time, it was wrongly dated as being made in 1327.

Vincent determined the document was sent to a British auction house in 1945 by a World War I flying ace who also defended Malta in World War II. The war hero, Forster Maynard, inherited the archives from Thomas and John Clarkson, who were leading campaigners against the slave trade.

William Lowther, hereditary lord of the manor of Appleby, was friends with Thomas Clarkson and possibly gave it him.

"There's a chain of connection there, as it were, a smoking gun, but there isn't any clear proof as yet that this is the Appleby Magna Carta. But it seems to me very likely that it is," Vincent said. He said he would like to find a letter or other documentation showing the Magna Carta was given to Thomas Clarkson.

A rare copy of the Magna Carta from 1300 sits in a display case April 15 at Harvard Law School in Cambridge, Mass.

Magna Carta relevant for a new generation

Vincent and Carpenter plan to visit Harvard in June to see its Magna Carta firsthand — and they say the document is as relevant as ever, as Harvard clashes with the Trump administration over how much authority the federal government should have over leadership, admissions and activism on campus.

"It turns up at Harvard at precisely the moment where Harvard is under attack as a private institution by a state authority that seems to want to tell Harvard what to do," Vincent said.

It's also a chance for a new generation to learn about the Magna Carta, which played a part in the founding of the United States — from the Declaration of Independence to the adoption of the Bill of Rights. Seventeen states incorporated aspects of it into their laws.

"We think of law libraries as places where people can come and understand the underpinnings of democracy," said Amanda Watson, the assistant dean for library and information services at Harvard Law School. "To think that Magna Carta could inspire new generations of people to think about individual liberty and what that means and what self-governance means is very exciting."

Our emails, ourselves: What the history of email reveals about us

Our emails, ourselves: What the history of email reveals about us

save_the_drama_for_your_mama@hotmail.com

magically_delicious_vic@hotmail.com

Gen Xers and millennials, in particular, have many embarrassing email addresses hidden in their digital closets. Still, it seemed like a good idea at the time. In the 1990s and early 2000s, the emergence of webmail services like Hotmail, Yahoo Mail, and AOL Mail fostered the unfettered creativity of a young generation that had yet to understand how technology would play into the rest of their lives. Email today permeates every aspect of our digitally driven society, from silly chain messages and professional correspondence to shopping promotions and malicious junk. To trace email's ascension to mainstream use, explored news coverage and cultural milestones to chart the evolution of email addresses and how they both shape and reflect our personalities.

Email technology began in the very practical halls of the United States government. It was part of a system established by the Department of Defense in the late 1960s. The Advanced Research Projects Agency Network connected computer users through a shared network rather than through dedicated and exclusive lines.

Government agencies and universities nationwide utilized ARPANET, and in 1971, computer engineer Ray Tomlinson sent the first test network email through ARPANET, using the underused @ symbol to separate the user's and host's names. Tomlinson did not remember his first messages or precisely which dates he sent them, saying that the content was "."

ARPANET provided the foundations for what we now know as the internet, where significant and insignificant messages are exchanged every minute of every day. In the years following the birth of email, the technology further developed and eventually became more accessible. Simple Mail Transfer Protocol, the networking standard for emails still used today, was built on concepts from ARPANET introduced in 1982. By 1988, Microsoft had released the first commercially available email client, Microsoft Mail.

Email in the wild: Beyond government and academia

In the 1990s, email use grew beyond universities and government agencies and into the public as the internet became widely available, and an increasing number of email clients (like Hotmail, Yahoo, and AOL mentioned above) emerged. By 1997, there were already 10 million users worldwide that had a free email account. Internet service providers gave households access to the World Wide Web through dial-up connections, requiring phone lines to work. Who of a certain age could ever forget the that signaled the start of a successful connection?

The internet became addicting, with family members regularly checking their emails, shopping, or talking in chat rooms, which could lead to household disputes over online usage and connection speeds. With these new types of personal online interactions, users became a lot more creative with how they identified themselves online, crafting pseudonyms and screen names instead of using their legal names as you would for a business email address.

As internet use became widespread, email caught on as a tool for communication, not just for personal use but also for business purposes. Email quickly became a cost-effective method for business functions like scheduling and validating shipments and transactions. Checking inboxes and composing and sending emails became a major component of the workday, and businesses soon developed practices for professional communication—from how to structure messages to when to divide time between work and personal messages.

An onslaught of messages in living color

The advent of HTML, or Hypertext Markup Language, helped spur the advancement of the internet and email as tools. HTML, the basic language of web content, helped add some color (quite literally) to emails, especially as businesses began using the technology for marketing purposes. Graphics, custom fonts, video, and other elements kept messages engaging for readers.

But some groups and individuals eventually found email technology troublesome—and quite annoying. As early as 1978, a marketing manager named Gary Thuerk sent a promotional message to about 400 users in ARPANET to promote a new computer product. While considered the first unsolicited "spam" message in history, it reportedly led to for his computer company.

As digital advertising and email marketing became prevalent in the late 1990s and early 2000s, with marketers tracking user data, governments began to regulate email and define several guidelines for using the medium. Enacted in 2003, the in the U.S. required companies to reduce unsolicited email efforts from companies, with measures demanding businesses give members clear ways to unsubscribe.

Before the rise of viral content and memes, information—usually dubious content and outright scams—would spread en masse to users through chain letters, encouraging readers to forward it to as many people as possible. Instant messaging services like AOL Instant Messenger, Internet Relay Chat, and Yahoo Messenger predated social media in connecting people globally, leading to new types of online interactions.

With all these new communication formats came new ways to identify oneself, usually with a pseudonym as a username—especially with the need to keep one's real name private. Some screen names could be based on childhood interests, such as poptardis@gmail.com for one Pop-Tarts lover and (faux) "Doctor Who" fan. Many came up with silly and sometimes regrettable pseudonyms for their email addresses, chat room names, or online gaming monikers, full of random numbers, characters, and pop culture references.

Society became accustomed to email and the internet as an informal means of everyday communication for work or frivolities, something to be taken for granted. However, as the 21st century progressed, the impact of technology on civilization became more evident.

Email on call, available 24/7

In 2004, Google launched its email client, appropriately titled Gmail. With a desire to provide a better web interface for email, help users sort through spam and promotions, and give them more storage space, Gmail eventually became one of the most popular email services, with by 2024.

With signature features like its social and promotions folders for inboxes, which automatically categorize the sometimes overwhelming number of emails received, Gmail ranks with other services like Apple Mail and Yahoo Mail as the most used email service today.

As of 2023, there are , a figure expected to grow to 4.89 billion by 2027. In 2023, about were sent and received every day globally. Formats like the email newsletter, which collects and aggregates information like news and other niche topics for audiences to digest, continued to evolve.

Another way emails have become more compact for consumers is by fitting email services onto mobile devices such as smartphones. Since BlackBerry disrupted the phone industry with devices that could be used to make phone calls, receive text messages, and check emails, a "mobile work era" commenced, and smartphones became essential for businesses. This trend only continued after the iPhone came onto the scene in 2007. Email formats soon evolved to suit smaller handheld screens.

Texting on phones has become one of the dominant forms of electronic communication, and direct messaging applications like the business-focused Slack and the personal service Facebook Messenger have grown in popularity. Even though these applications have similar functions, email has remained a prominent form of communication for businesses and personal use. It is a great leveler for digital communication. Not everyone may have a Slack account or habitually check Messenger, but they would more likely have an email address.

The use of emails for work, leisure, and marketing continues in the age of social media, artificial intelligence, and an influx of applications. Emails are becoming automated, with personalized marketing content based on customer actions such as signing up for a service or purchasing a product. Customer data tied to email addresses, too, are becoming a commodity, sliced, diced, and scrutinized to gain ground on a corporate target. Even as companies seek data from consumers, users are becoming more wary of sharing their email addresses with organizations, keeping their inboxes clean of clutter in a time where information comes at us from every direction.

Story editing by Carren Jao. Copy editing by Paris Close. Photo selection by Lacy Kerrick.

originally appeared on and was produced and distributed in partnership with Stacker Studio.